I read a lot of research articles. Both to stay up to date within the fields I am working in, and some just for personal curiosity. A lot of times I wish there was a much shorter, and easy to digest summary. This is what I want to create for select articles with these ABC (Article Breakdown and Commentary) posts.

To start off easy I am choosing an article I co-authored, the one with the very long title above [1].

Background and relevancy

One of the biggest challenges in development of topical treatments is to measure how much of the drug actually cross the skin barrier and makes it into the right skin compartments to exert its effect. This is called pharmacokinetics: how fast, and how much of a drug actual ends up where I want it to.

Most of the techniques to study topical pharmacokinetics will be invasive (need a biopsy), be destructive (kill the sample material) and/or does not provide the cellular resolution to really understand where the drug is going. In addition, when taking a biopsy you often end up pushing the drug into the sample as you take the biopsy, invalidating the downstream measurements. Furthermore, most current imaging technologies only provide a temporal snapshot, limiting the spatial information.

An optimized system would be one that captured both the skin structure at a cellular level, and the drug concentration, did so at distinct layers in the skin, and in real-time without altering the sample. The article [1] showcases an attempt to build such a system.

Real-time readings matter

When creating topical treatments the formulation contains a variety of penetration enhancers to stabilize the drug and aid in its dermal penetration. However, we rarely understand how and why a given formulation vehicle is better than another, as we have been limited to measuring the resulting drug concentration at a given skin layer, or even on the other side of a skin-like membrane (Franz cell).

Imagine we instead had a video showing us: across the different skin layers, how the structure of the skin changed, if the drug permeated via the sebaceous glands or across the stratum corneum or some third mechanism, and where the drug deposited, and at what time point after application.

This would allow us a better understanding of how different formulations altered the dermal penetration. And potentially lead to development of formulations with more targeted delivery and increasing the drug’s bioavailability. In some cases the bioavailability can be changed eight-fold just based on the formulation system [2].

PK, SRS and Deep learning

As mentioned, to create a more optimal understand of PK (pharmacokinetics, where the drug goes at what time) we need a non-invasive, real-time measurement of the drug in the skin. One such measurement technique is SRS (stimulated Raman scattering). This imaging technique sends in light at a given wavelength, which based on the specific wavelength, makes specific biomolecules “vibrate” and send out another wavelength. The SRS can thus be tuned to “see” different, but limited, number of biomolecules, and can further be tuned to do so at different depth in the skin.

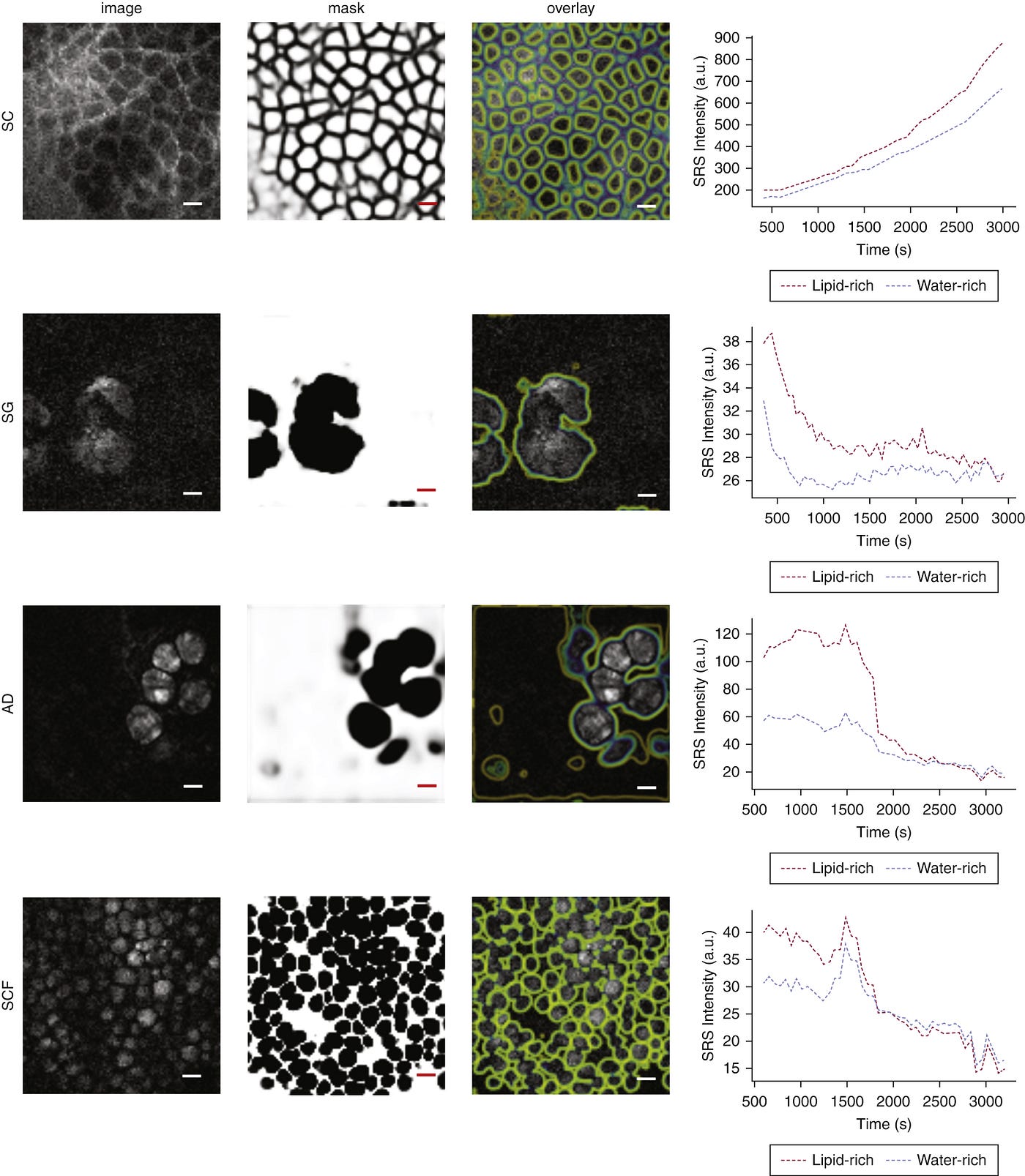

In this work [1] it was tuned to look for lipid rich (cell membranes) and lipid poor (all the rest) regions, as well as the drugs investigated, and at depths of 0–10, 20–40, 40–70, and 90–100 µm. This then creates a z-stack of images with outlines of the cell membranes and containing the signals needed to quantify drug concentrations, allowing for a pseudo-3D understanding of the skin structure and drug deposits.

With the system doing a full scan of the skin every 60 seconds there is a need for automated analysis. Specifically, we want to create higher contrast images showing the cellular structures, and how they change over time. Convolutional networks and in particular Unets [3], are an excellent choice for this type of image segmentation. Such a network was trained to take the SRS images and turn them into binary masks outlining the cell membranes.

Now we were able to see not only the cellular changes, but also overlay the drug concentrations in a pixel based manner to determine if the drug was primarily associated with the lipid rich or lipid poor regions. In other words, how was the drug’s chemical characteristics in combination with the formulation and cellular structure affecting the penetration.

The above shows an example of the cell membrane outlines, and the drug concentration over time associated with either cell membranes or water.

Formulations change the skin structure

In the article we tested two different formulations, a naive solvent and a gel-like formulation optimized for increase skin penetration of the drug. In the naive solvent the drug deposited in the stratum corneum, and penetrated into the deeper skin layers via the sebaceous glands. However, the gel induced changes to the stratum corneum and formed a pore-like structure increasing the ability of the drug to penetrate, leading to a far more rapid diffusion in this skin layer.

Measured at the deeper skin layers, the drug concentrations of the naive solvent and gel formulation were identical, showing that without a layer and time dependent measurement the differences in the penetration behaviour would have been undetectable.

In other words, the presented system or tooling, allowed for much better insights into the mechanisms of how penetration enhancers can alter drug transport pathways.

Limitations and future development

The system presented in the article operated at one frame per second, limiting the time resolution of the drug absorption, as multiple fields of view and depths were scanned. Also not all compounds have the required unique molecular structures to allow for this type of “vibrational” imaging. Most natural compounds do not, and requires the incorporation of heavy atoms to allow for tracking. One of the limiting factors for increasing both frame rate and allowing for tracking of more types of molecules is the tuning speed of the light source. With the development of more rapid tuning these restrictions will disappear.

Lastly, the presented system is large, and not applicable to measurements in patients. Development of more portable systems would allow for direct mechanistic understanding in a clinical trial setting and provide a lens with which we can start to develop a better understanding of how individual differences in skin impact drug delivery. We know that there are gender and site differences in skin and hence absorption rates [4], and that water content, pH, age and other factors have an impact, but we have yet to develop our understanding how how all of these factors interplay with the multitude of different formulation options.

I am very excited to follow the development of such real-time systems, and see if systematic approaches for studying the interplay between skin characteristics, drugs, and formulation vehicles can be developed to capture the foundational data needed for better predictive models.

References:

[1] Feizpour, Amin, Troels Marstrand, Louise Bastholm, Stefan Eirefelt, and Conor L. Evans. “Label-free quantification of pharmacokinetics in skin with stimulated Raman scattering microscopy and deep learning.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 141, no. 2 (2021): 395–403.

[2] Kreilgaard, Mads. “Dermal pharmacokinetics of microemulsion formulations determined by in vivo microdialysis.” Pharmaceutical research 18 (2001): 367–373.

[3] Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. and Brox, T., 2015. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18 (pp. 234–241). Springer International Publishing.

[4] Polak, Sebastian, Cyrus Ghobadi, Himanshu Mishra, Malidi Ahamadi, Nikunjkumar Patel, Masoud Jamei, and Amin Rostami-Hodjegan. “Prediction of concentration–time profile and its inter-individual variability following the dermal drug absorption.” Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 101, no. 7 (2012): 2584–2595.